Central Dogma: DNA, RNA, and Protein Explained

Introduction: The Master Plan of Life

Life, in its incredible diversity and complexity, is ultimately governed by a remarkably elegant and universal set of molecular instructions encoded within every cell. At the heart of this biological masterpiece lies the Central Dogma of Molecular Biology, a concept first articulated by Francis Crick in 1958, which describes the flow of genetic information within a biological system. This dogma maps the essential pathway by which the long-term archival instructions, stored securely in the cell’s DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid), are first copied into a working molecular blueprint, known as RNA(Ribonucleic Acid). Subsequently, this temporary blueprint is used to construct the functional workhorses of the cell: the proteins. This fundamental process ensures that the vast genetic potential contained within the nucleus is safely and accurately translated into the thousands of specific enzymes, structural components, and signaling molecules necessary for the organism’s survival, growth, and reproduction.

The pathway from gene to function is not a simple linear transfer but a tightly regulated, complex cascade involving numerous specialized molecules and sophisticated cellular machinery. Errors at any stage of this delicate process—from the initial copying of the DNA sequence to the final folding of the protein—can lead to severe cellular dysfunction and disease, underscoring the vital importance of this pathway. Understanding the Central Dogma is therefore not just an academic exercise; it is the key to unlocking the secrets of inherited diseases, developing targeted drug therapies, and harnessing the power of biotechnology. This molecular journey, encompassing replication, transcription, and translation, forms the unbreakable chain that links the inherited genetic code to the dynamic observable traits of an organism.

This extensive guide will take you step-by-step through the Central Dogma, detailing the processes that govern the flow of genetic information within the cell. We will meticulously break down the intricacies of DNA replication, the nuanced phases of transcription into RNA, and the complex mechanics of translation into protein. Finally, we will explore the critical roles of proteins themselves and discuss the modern scientific breakthroughs that have expanded—but not broken—this foundational concept of molecular biology.

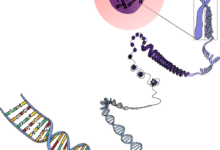

1. The Repository: DNA and Genetic Storage

The journey begins with DNA, the double-stranded molecule that serves as the stable, long-term genetic repository, securely storing the code for all proteins and regulatory elements.

DNA is the cell’s master library, holding all the essential instructions.

A. The Double Helix Structure

DNA is defined by The Double Helix Structure. It is composed of two long strands coiled around each other, forming the famous helix shape.

This structure, discovered by Watson and Crick, is stabilized by chemical bonds between complementary base pairs.

B. Base Pairing Rules

The genetic code is maintained by strict Base Pairing Rules. Adenine (A) always pairs with Thymine (T), and Guanine (G) always pairs with Cytosine (C).

This complementarity ensures that each strand of the helix contains the necessary information to reconstruct the other strand.

C. Function as Genetic Archive

DNA’s primary purpose is its Function as Genetic Archive. Its double-stranded structure makes it extremely stable and highly resistant to chemical degradation or accidental mutation.

This stability is essential because DNA must last the entire life of the cell and be passed perfectly to daughter cells.

D. The Genome Organization

The DNA is organized into The Genome Organization. In humans, the DNA is packaged into 46 linear structures called chromosomes, located safely inside the cell nucleus.

The genome contains both protein-coding regions (genes) and vast non-coding regulatory regions.

2. Replication: Duplicating the Archive

Before a cell can divide, its entire genetic library (DNA) must be duplicated with near-perfect fidelity through a process known as Replication.

Replication ensures that every new cell receives a complete and identical copy of the genetic instructions.

E. Semi-Conservative Mechanism

DNA replication operates via the Semi-Conservative Mechanism. When the double helix is copied, each new DNA molecule consists of one old (parental) strand and one newly synthesized (daughter) strand.

This mechanism ensures that the original sequence is preserved across generations of cells.

F. Initiation at the Origin

The process starts with Initiation at the Origin. Specific enzyme complexes, including the enzyme helicase, unwind and separate the two parental DNA strands at specific sequences called the origins of replication.

This separation creates a replication bubble with two Y-shaped replication forks moving in opposite directions.

G. DNA Polymerase Action

The core copying enzyme is DNA Polymerase Action. This enzyme moves along the parental strand, reading the sequence and synthesizing the new complementary strand by adding free nucleotides.

DNA polymerase is highly accurate, possessing built-in proofreading functions that correct errors immediately.

H. Leading and Lagging Strands

Replication involves synthesizing Leading and Lagging Strands simultaneously. The leading strand is synthesized continuously in one piece because DNA polymerase can move in the correct direction (5′ to 3′).

The lagging strand is synthesized discontinuously in short segments, requiring additional enzymes to fill the gaps and stitch the segments together.

3. Transcription: From DNA to RNA Blueprint

Transcription is the process where the genetic information from a specific gene sequence in the DNA is copied into a temporary messenger molecule called mRNA (messenger RNA).

Transcription is like creating a disposable, working copy of the original master plan.

I. RNA Polymerase as the Key

The primary enzyme in this process is RNA Polymerase as the Key. Unlike DNA polymerase, RNA polymerase does not require a primer and reads only one of the two DNA strands (the template strand).

The enzyme synthesizes the new RNA molecule using the base pairing rules, but substituting Uracil (U) for Thymine (T).

J. Initiation, Elongation, and Termination

Transcription proceeds in three phases: Initiation, Elongation, and Termination. Initiation involves the RNA polymerase binding to a specific starting sequence, the promoter.

During elongation, the RNA polymerase moves along the gene, extending the RNA strand. Termination occurs when the polymerase encounters a specific signal and detaches.

K. Pre-mRNA Processing

In eukaryotic cells, the immediate product undergoes extensive Pre-mRNA Processing. The initial transcript, or pre-mRNA, contains non-coding regions called introns and coding regions called exons.

Introns must be removed, and exons must be spliced together to create the mature, functional mRNA.

L. Alternative Splicing

A sophisticated mechanism is Alternative Splicing. The cell can splice the same pre-mRNA molecule in different ways, joining different combinations of exons.

This allows a single gene to code for multiple distinct protein variants, greatly expanding the effective size of the genome.

M. mRNA Function and Export

The final, mature mRNA Function and Export is to carry the genetic message. The mRNA exits the nucleus through nuclear pores and travels to the cytoplasm.

In the cytoplasm, the mRNA molecule serves as the direct template for protein synthesis.

4. Translation: From RNA to Protein

Translation is the crucial final step of the Central Dogma, where the nucleotide sequence encoded in the mRNA is decoded to specify the precise sequence of amino acids in a polypeptide chain (protein).

Translation is the actual construction of the functional molecule based on the blueprint.

N. Ribosomes as the Workbenches

Protein synthesis occurs on Ribosomes as the Workbenches. These complex molecular machines, made of RNA and protein, are found free in the cytoplasm or bound to the endoplasmic reticulum.

The ribosome physically holds the mRNA template and coordinates the assembly of the amino acid chain.

O. Transfer RNA (tRNA) Adapters

The decoding is performed by Transfer RNA (tRNA) Adapters. Each tRNA molecule carries a specific amino acid on one end and has a complementary three-nucleotide sequence (anticodon) on the other.

The tRNA acts as the molecular bridge, matching the amino acid to the correct codon on the mRNA.

P. The Genetic Code and Codons

The entire system relies on The Genetic Code and Codons. The mRNA message is read in successive groups of three nucleotides, called codons.

The genetic code is nearly universal, meaning a specific codon specifies the same amino acid in almost all organisms.

Q. The Start and Stop Signals

Translation requires The Start and Stop Signals. The codon AUG acts as the universal start signal, always specifying the amino acid Methionine (Met).

Specific stop codons (UAA, UAG, UGA) signal the ribosome to release the completed polypeptide chain.

R. Elongation Cycle

The process of building the protein is the Elongation Cycle. The ribosome moves along the mRNA, reading one codon at a time. A matching tRNA delivers its amino acid, and the ribosome catalyzes the formation of a peptide bond with the growing chain.

This cycle repeats until the stop codon is reached, sequentially assembling the protein.

5. Post-Translational Modification and Protein Function

The newly formed polypeptide chain is not immediately functional; it must undergo folding and modification to become a three-dimensional, active protein capable of performing its job.

The shape of a protein dictates its function, and folding is crucial.

S. Protein Folding and Structure

Immediate action is Protein Folding and Structure. The linear chain of amino acids spontaneously folds into a complex three-dimensional shape, often guided by helper proteins called chaperones.

The final shape determines the protein’s function, categorized into primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures.

T. Chemical Modifications

Proteins undergo diverse Chemical Modifications. These post-translational modifications (PTMs) include the addition of chemical groups like phosphate (phosphorylation), sugar groups (glycosylation), or lipids.

PTMs often act as regulatory switches, turning the protein on or off or directing it to a specific location.

U. Protein Targeting and Trafficking

Proteins are directed by Protein Targeting and Trafficking. Specialized signal sequences within the polypeptide chain act as “zip codes,” directing the protein to its final cellular destination.

These destinations can include the cell membrane, various organelles (like mitochondria), or export outside the cell.

V. Function as Cellular Workhorses

Proteins serve their primary Function as Cellular Workhorses. They execute virtually all cellular functions, acting as enzymes (catalyzing reactions), structural components, transport channels, hormones, and immune factors.

The entire observable phenotype of an organism is ultimately determined by the collective function of its proteins.

6. Expanding the Central Dogma

While the DNA-to-RNA-to-Protein pathway remains the central tenet, modern discoveries have identified important exceptions and variations, particularly involving the role of RNA.

Biological reality is sometimes more complex than the original, simple model.

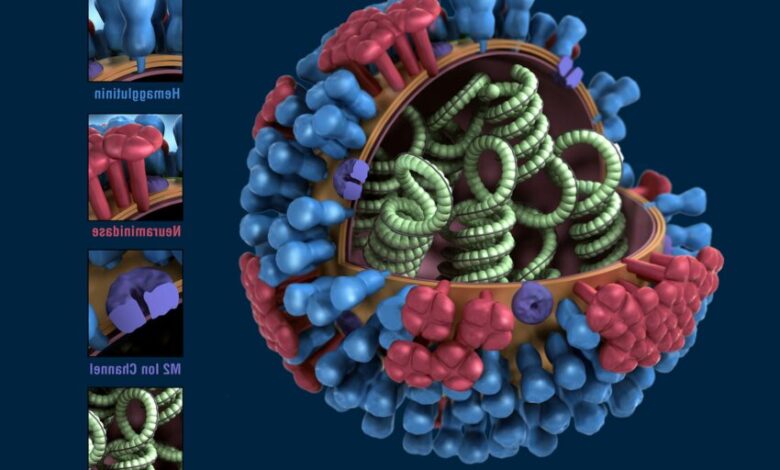

W. Reverse Transcription

The first major exception is Reverse Transcription. Certain viruses, most notably retroviruses like HIV, use an enzyme called reverse transcriptase to synthesize DNA from an RNA template.

This process essentially reverses the flow of information back from RNA to DNA, which then integrates into the host genome.

X. RNA Replication

Another exception is RNA Replication. Some viruses (RNA viruses) entirely bypass the DNA stage, using an RNA template to synthesize new RNA directly, catalyzed by an enzyme called RNA replicase.

This demonstrates that RNA can act as both the template and the archive in certain life forms.

Y. Non-coding RNA Roles

Modern research highlights Non-coding RNA Roles. Many RNA molecules, such as tRNA, rRNA, microRNAs (miRNAs), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), are never translated into protein.

Instead, they perform crucial regulatory functions, controlling gene expression by silencing mRNA or modifying chromatin structure.

Z. Epigenetic Regulation

The entire process is overlaid with Epigenetic Regulation. Chemical modifications to the DNA (like methylation) or to the histone proteins control which genes are accessible for transcription in the first place.

Epigenetics dictates when and where the Central Dogma is allowed to proceed.

AA. Prions and Misfolding

The existence of Prions and Misfolding challenges the protein-only aspect. Prions are infectious proteins that cause disease by inducing normally folded proteins to misfold into an aberrant, disease-causing structure.

This transfer of structural information from protein to protein occurs without involving the genetic code.

Conclusion: Life’s Unbreakable Code

The Central Dogma of Molecular Biology accurately describes the universal flow of genetic information that dictates all life, moving sequentially from the stable archive of DNA to the temporary blueprint of RNA and finally to the functional product, protein. The process of replication ensures the precise duplication of the genetic code, while transcriptionutilizes RNA polymerase to create the necessary mRNA template.

The final, complex step of translation involves ribosomes and tRNA adapters accurately converting the mRNA’s codons into a specific sequence of amino acids. The resulting polypeptide chain must undergo precise protein folding and structure to achieve its functional three-dimensional shape.