Cellular Immortality: Decoding Mitosis and Cell Life

Introduction: The Unseen Machinery of Life

Every living organism, from the smallest bacterium to the largest blue whale, is fundamentally built upon the continuous, coordinated activity of its cells. These tiny, self-contained units are the true architects of life, constantly engaged in a silent, dynamic process of growth, function, and, most critically, reproduction. The process by which a single parent cell divides to produce two genetically identical daughter cells is known as mitosis, a marvel of biological precision that ensures the seamless continuity of life. Without this highly regulated mechanism, multicellular organisms could neither grow from a fertilized egg nor repair damaged tissues after injury; indeed, the very stability of the organism’s genetic information across generations of cells would be compromised. Mitosis is far more than simple division; it is an elaborate, choreographed dance of chromosomes that requires countless molecular checkpoints and structural components to execute perfectly, a process so crucial that errors often lead directly to catastrophic diseases like cancer.

The ability of a cell to precisely duplicate its entire genome and allocate a perfect copy to each new cell is the secret to both growth and maintenance. Beyond this normal cycle of division and repair, scientists also study the mechanisms that allow some cells, particularly those involved in cancerous growth, to achieve a state resembling cellular immortality. This phenomenon involves bypassing the natural limits on division imposed by the shortening of telomeres and disabling the molecular brakes that normally induce programmed cell death, or apoptosis. Understanding the intricate details of the cell cycle, from the preparation phases to the final division, provides the foundational knowledge required to comprehend development, tissue regeneration, and, most importantly, the pathological pursuit of unending growth seen in malignant tumors.

This extensive guide will delve into the secret life of cells, meticulously breaking down the precise phases of mitosis and the entire cell cycle that governs it. We will explore the critical checkpoints that maintain genomic integrity and then examine the cellular mechanisms, particularly the role of telomerase, that grant cancer cells their near-immortal capabilities. By decoding the fundamental processes of cellular life and division, we unlock profound insights into development, aging, and the perpetual struggle against disease.

1. The Cell Cycle: Life’s Perpetual Motion

Before a cell can undergo division (M-phase), it must first complete a complex and highly regulated series of preparatory steps known collectively as the Cell Cycle.

The cell cycle is the ordered series of events that culminates in cell division.

A. Interphase: Preparation for Division

The cycle begins with Interphase: Preparation for Division, which is the longest phase, often lasting over $90\%$ of the cell’s lifespan. Interphase is divided into three distinct sub-phases.

During interphase, the cell is metabolically active, growing in size and synthesizing essential materials.

B. G1 Phase: Growth and Monitoring

The first sub-phase is the G1 Phase: Growth and Monitoring (“Gap 1”). During G1, the cell increases its mass, synthesizes proteins and organelles, and monitors its environment.

The cell checks for necessary growth signals and assesses whether the DNA is intact before committing to replication.

C. S Phase: DNA Synthesis

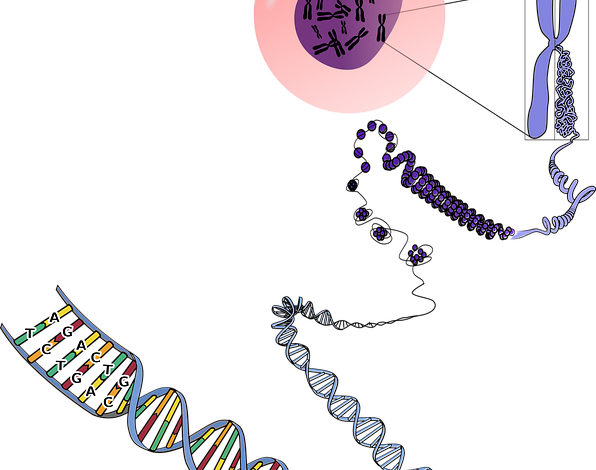

Next is the S Phase: DNA Synthesis (Synthesis phase). This is the crucial stage where the cell replicates its entire genome.

Each chromosome is precisely duplicated, resulting in two identical sister chromatids joined at the centromere.

D. G2 Phase: Final Checks

The final preparation stage is the G2 Phase: Final Checks (“Gap 2”). The cell ensures that DNA replication is complete and checks for any damage that may have occurred during the S phase.

The cell also synthesizes the proteins necessary to build the mitotic spindle, the machinery required for chromosome separation.

E. M Phase: Division

The culminating event is the M Phase: Division (Mitotic phase). This phase encompasses both mitosis (nuclear division) and cytokinesis (cytoplasmic division).

M phase is typically the shortest stage of the cell cycle but is the most visually dramatic.

2. Mitosis: The Choreographed Nuclear Division

Mitosis is the meticulous five-stage process of nuclear division that ensures each daughter cell receives a perfectly equal and identical set of chromosomes.

Mitosis is an elegant, highly structured distribution system for genetic material.

F. Prophase: Condensation and Spindle Formation

The first mitotic stage is Prophase: Condensation and Spindle Formation. The diffuse chromatin begins to coil and condense into visible, distinct chromosomes, each consisting of two sister chromatids.

The centrosomes (which contain the centrioles) begin to migrate to opposite poles of the cell, initiating the formation of the mitotic spindle apparatus.

G. Prometaphase: Breakdown and Attachment

Prometaphase: Breakdown and Attachment marks the dissolution of the nuclear envelope, allowing the spindle microtubules to enter the nuclear area.

Microtubules attach to the chromosomes at the kinetochore, a protein structure located at the centromere of each sister chromatid.

H. Metaphase: Alignment at the Plate

The most critical alignment stage is Metaphase: Alignment at the Plate. The attached spindle fibers pull and push the chromosomes until they are all precisely lined up along the cell’s central plane, called the metaphase plate.

This alignment is essential to ensure that sister chromatids separate correctly in the next stage.

I. Anaphase: Separation of Chromatids

Anaphase: Separation of Chromatids is the phase of action, marked by the simultaneous separation of all sister chromatids. The protein “glue” holding them together is cleaved.

Once separated, each chromatid is considered a full-fledged, individual chromosome, and they are rapidly pulled toward opposite spindle poles.

J. Telophase: De-condensation and Reformation

The final stage is Telophase: De-condensation and Reformation. The separated chromosome sets arrive at the poles and begin to de-condense back into diffuse chromatin.

New nuclear envelopes form around the two separate chromosome sets, creating two distinct nuclei within the single parent cell.

3. Cytokinesis: Dividing the Cytoplasm

Cytokinesis is the physical process that follows mitosis, completing cell division by partitioning the cytoplasm and organelles into two new daughter cells.

Cytokinesis is the final, essential step in producing two viable, separate cells.

K. The Contractile Ring

In animal cells, the division is driven by The Contractile Ring. This ring, made of actin and myosin filaments (similar to muscle fibers), forms just beneath the plasma membrane at the metaphase plate.

The ring contracts like a purse-string, pinching the cell in two.

L. Cleavage Furrow Formation

The contraction results in Cleavage Furrow Formation. This is the visible indentation around the cell’s equator that deepens progressively until the two daughter cells are completely separated.

This process ensures that each new cell receives a portion of the original cytoplasm and organelles.

M. Plant Cell Plate Formation

Division differs in plants, requiring Plant Cell Plate Formation. Because plant cells have a rigid cell wall, they cannot pinch in two.

Instead, vesicles derived from the Golgi apparatus fuse in the center of the cell to form a cell plate, which eventually develops into a new cell wall separating the daughter cells.

4. Checkpoints: Maintaining Genomic Integrity

![]()

The cell cycle is not simply a linear march; it is controlled by a highly sophisticated internal surveillance system composed of molecular checkpoints that prevent division if errors are detected.

These checkpoints act as the quality control system for cellular reproduction.

N. G1 Checkpoint: The Restriction Point

The most critical control point is the G1 Checkpoint: The Restriction Point. This checkpoint determines whether the cell is committed to dividing or will enter a non-dividing state (G0 phase).

The cell checks for adequate size, nutrients, growth factors, and, most importantly, undamaged DNA before proceeding to the S phase.

O. G2/M Checkpoint: Replication Fidelity

The G2/M Checkpoint: Replication Fidelity ensures that the cell is ready for mitosis. This checkpoint prevents the initiation of M-phase until DNA replication has been completed accurately.

It acts as a final safeguard against entering mitosis with incomplete or damaged chromosomes.

P. M (Spindle) Checkpoint: Chromosome Attachment

The M (Spindle) Checkpoint: Chromosome Attachment operates during metaphase. It ensures that every single kinetochore is properly attached to a spindle microtubule before anaphase begins.

This is vital to prevent aneuploidy (daughter cells having the wrong number of chromosomes), a common characteristic of cancer.

Q. Cyclins and Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (Cdks)

The checkpoint timing is regulated by complexes of Cyclins and Cyclin-Dependent Kinases (Cdks). Cyclins are proteins whose concentration fluctuates throughout the cycle.

Cdks are enzymes that, when activated by binding to cyclins, phosphorylate target proteins to drive the cell forward into the next phase.

R. Tumor Suppressor Genes (p53)

Key to control are Tumor Suppressor Genes (p53). The p53 protein is often called the “guardian of the genome” because it halts the cell cycle at the G1 checkpoint if DNA damage is detected.

If the damage is irreparable, p53 initiates apoptosis (programmed cell death), preventing the damaged cell from dividing.

5. Cellular Senescence and Immortality

Normal cells have a finite capacity for division, a limit imposed by telomeres. Cancer cells often bypass this limit, achieving a form of unregulated, sustained proliferation or “immortality.”

The quest for immortality is both a natural limit on healthy cells and the hallmark of cancer.

S. The Telomere Shortening Clock

Cellular aging is governed by The Telomere Shortening Clock. Telomeres are repetitive DNA sequences located at the ends of linear chromosomes, protecting the genome from degradation and fusion.

With each round of division, telomeres naturally shorten, acting as an internal countdown timer for the cell.

T. The Hayflick Limit

This shortening enforces The Hayflick Limit, the observation that normal human cells can divide only a limited number of times (typically 40–60 divisions) before entering a permanent non-dividing state called senescence.

Senescence is a protective mechanism to prevent cells with critically shortened telomeres from becoming cancerous.

U. Telomerase Reactivation

The key to cellular immortality is Telomerase Reactivation. Telomerase is an enzyme that synthesizes telomere DNA, counteracting the natural shortening process.

While telomerase is highly active in germ cells and stem cells, it is virtually silent in most mature somatic cells.

V. Cancer’s Molecular Strategy

Cancer’s Molecular Strategy is to forcibly reactivate the telomerase enzyme. By rebuilding and maintaining their telomere length, cancer cells effectively reset the Hayflick limit, achieving indefinite replicative potential.

This reactivation is detected in over $85\%$ of all human cancers, making telomerase a major drug target.

W. Evasion of Apoptosis

Immortality also requires Evasion of Apoptosis. Cancer cells must not only divide indefinitely but also overcome the molecular signals, often triggered by p53, that command them to self-destruct due to damage or stress.

They often achieve this by disabling tumor suppressor pathways or overexpressing anti-apoptotic proteins.

6. Applications in Medicine and Research

Understanding the tightly regulated dance of the cell cycle and the mechanisms of cellular immortality is crucial for advancing medical treatments, particularly for age-related diseases and cancer.

The cell cycle is a therapeutic target as much as it is a biological process.

X. Cancer Chemotherapy Targeting

Traditional Cancer Chemotherapy Targeting exploits the speed of the cell cycle. Many chemotherapy drugs target rapidly dividing cells by interfering with DNA replication (S phase) or spindle formation (M phase).

While effective, this indiscriminate approach also harms rapidly dividing healthy cells, such as those in hair follicles or bone marrow.

Y. Targeted Cell Cycle Inhibitors

Modern research focuses on Targeted Cell Cycle Inhibitors. These drugs aim to specifically block the hyperactive Cdks or cyclins that are driving unregulated division in cancer cells.

This approach offers the potential for highly selective treatment with fewer severe side effects than conventional chemotherapy.

Z. Senolytics for Anti-Aging

The study of senescence leads to Senolytics for Anti-Aging. Senolytic drugs are designed to selectively induce apoptosis in senescent cells, which accumulate with age and contribute to inflammation and tissue dysfunction.

Clearing these old, dysfunctional cells could potentially extend health span and prevent age-related diseases.

AA. Regenerative Medicine

Control over the cell cycle is fundamental to Regenerative Medicine. Understanding the molecular signals that prompt quiescent cells (those in G0) to re-enter the cycle is key to stimulating tissue repair.

This knowledge is used to encourage stem cells to divide and differentiate to replace damaged tissue.

BB. Understanding Aneuploidy

The spindle checkpoint research is vital for Understanding Aneuploidy. This condition, where cells have an abnormal number of chromosomes, is characteristic of most solid tumors and is often the result of checkpoint failure.

Developing drugs to strengthen or repair the spindle checkpoint could prevent the genetic chaos seen in malignant cells.

Conclusion: The Mastery of Replication

The mastery of cell replication, centered on the elegant process of mitosis, is the fundamental engine driving the growth, maintenance, and repair of all multicellular life. This intricate process is governed by the highly regulated cell cycle, which relies on sequential molecular checkpoints to ensure the perfect duplication and segregation of the genome.

Errors in these checkpoints, often involving key players like p53, can lead to uncontrolled proliferation, while the forced telomerase reactivation allows cancer cells to bypass the natural limit imposed by the Hayflick limit, achieving a form of cellular immortality. Modern medicine is now directly targeting these mechanisms, utilizing targeted cell cycle inhibitors and exploring senolytics for anti-aging to control both undesirable cell growth and age-related decline.