CRISPR: Rewriting Life’s Code with Precision Editing

Introduction: The Dawn of Genomic Editing Revolution

For decades, scientists have dreamed of possessing a tool capable of editing the very blueprint of life—the genome—with the surgical precision of a text editor, allowing them to correct faulty genes responsible for debilitating human diseases, enhance crop resilience, and unlock fundamental biological secrets. While early genetic engineering techniques offered limited, often clumsy methods of inserting foreign DNA, they lacked the speed, accuracy, and versatility required to truly manipulate the complex, vast code contained within an organism’s cells. The discovery of CRISPR-Cas9, a naturally occurring defense system found in bacteria, suddenly transformed this dream into a reality, providing molecular biologists with an unprecedented instrument for the rapid and affordable modification of virtually any organism’s DNA. This breakthrough, first widely adopted in the early 2010s, quickly accelerated genetic research far beyond what was previously imaginable, democratizing access to powerful genomic tools and launching the world into a new era of biology.

CRISPR-Cas9 is not just an incremental improvement; it represents a fundamental paradigm shift in molecular biology, often described as the most important biological discovery of the 21st century. At its core, it is a simple yet elegant mechanism: a guide RNA molecule locates the desired target sequence within the vast stretches of DNA, and a corresponding Cas9 enzyme acts as the molecular scissors, precisely cutting the DNA helix at that exact location. Once the DNA is cut, the cell’s natural repair mechanisms kick in, which scientists can hijack to either disable the target gene (a “gene knockout”) or insert a new, corrected sequence (gene correction or “knock-in”). The power of this technology lies in its customizability and its ability to work across all forms of life, from bacteria and plants to human cells.

This extensive guide will delve into the ingenious mechanisms of CRISPR Technology, explaining its bacterial origins and detailing the process of precision editing that allows scientists to rewrite the code of life. We will meticulously cover the profound applications of CRISPR across medicine, agriculture, and fundamental research, while also engaging with the critical ethical considerations and the emerging next-generation CRISPR tools that promise to refine its power even further. Mastering this technology is essential for understanding the future of disease treatment and biological innovation.

1. The Ingenious Origins of CRISPR

The revolutionary technology used in labs today was originally discovered not in a sophisticated research institution, but as a robust and ancient immune system utilized by bacteria to defend themselves against viral invaders.

Nature developed the ultimate gene editing tool long before humans ever conceptualized it.

A. Bacterial Immunity Role

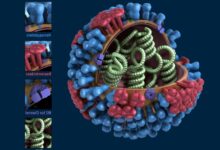

CRISPR’s fundamental role is in Bacterial Immunity Role against viruses (phages). When a bacterium survives a viral attack, it saves a small snippet of the invader’s DNA.

These snippets are stored within the bacterium’s genome in specific clusters known as CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats).

B. The Cas Enzyme Defense

These stored viral sequences are then used by the Cas Enzyme Defense system. If the same virus attacks again, the bacterium transcribes the stored snippet into a small guide RNA (gRNA) molecule.

The guide RNA then pairs with a Cas enzyme, forming a complex that patrols the cell for matching viral DNA.

C. Molecular Scissors Action

The Cas enzyme performs the Molecular Scissors Action. Upon finding a perfect match to the guide RNA, the Cas enzyme—typically Cas9—executes a double-strand break, precisely cutting the viral DNA and neutralizing the threat.

This highly specific and efficient defense mechanism is what scientists realized they could repurpose as a programmable gene editor.

D. Repurposing the System

The great breakthrough involved Repurposing the System for human use. Researchers realized they could design their own synthetic guide RNA (sgRNA) to target any DNA sequence they wished, rather than just viral DNA.

By injecting the customized sgRNA and the Cas9 enzyme into a cell, they gained the power to cut the genome at any target location.

2. The Mechanics of Precision Gene Editing

The core appeal of CRISPR-Cas9 lies in its remarkable simplicity and its two key components: the customizable guide RNA and the DNA-cutting enzyme. The system harnesses the cell’s natural instincts to repair damage.

The elegance of the two-part system is what makes CRISPR so versatile and easy to use.

E. Guide RNA (gRNA) Specificity

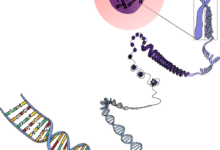

The efficiency relies on Guide RNA (gRNA) Specificity. This short synthetic RNA molecule is engineered to be complementary to a 20-nucleotide target sequence in the DNA where the edit is desired.

The gRNA ensures that the Cas9 enzyme is directed to that single, unique spot within the billions of nucleotides in the cell’s genome.

F. The Cas9 Enzyme Action

The Cas9 Enzyme Action is the next step. Cas9 is the protein that carries the gRNA, scanning the DNA until the guide successfully binds to the target sequence.

Once bound, Cas9 changes its conformation and cuts both strands of the DNA helix, creating a highly specific double-strand break (DSB).

G. Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM)

Successful targeting requires a crucial sequence called the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). This is a short, specific sequence (typically NGG) that must immediately follow the target site.

Cas9 cannot bind and cut the DNA unless this specific PAM sequence is present right next to the target site.

H. Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ)

When the cut is made, the cell attempts repair via Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ). This is the cell’s quickest, but error-prone, repair mechanism that attempts to stitch the two broken ends back together immediately.

This repair often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cut site, which typically deactivates, or “knocks out,” the targeted gene.

I. Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

For precise gene correction, scientists utilize Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). This is a rarer, more accurate repair pathway that occurs when a template DNA molecule is provided.

By supplying a template with the desired correction, the cell uses it to accurately patch the break, effectively inserting the new DNA sequence.

3. Revolutionary Applications in Human Health

The most dramatic promise of CRISPR lies in its potential to cure genetic disorders and revolutionize disease modeling, diagnostics, and therapy development.

CRISPR offers a tangible hope for millions suffering from inherited diseases.

J. Gene Therapy for Inherited Disorders

CRISPR is a leading tool for Gene Therapy for Inherited Disorders. Diseases caused by a single faulty gene, such as sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, and muscular dystrophy, are prime targets.

Scientists aim to remove the patient’s own cells, correct the defective gene using HDR, and then reinfuse the corrected, healthy cells back into the patient.

K. Enhancing Cancer Immunotherapy

The technology is crucial in Enhancing Cancer Immunotherapy. CRISPR can be used to engineer a patient’s T-cells (immune cells) to specifically recognize and aggressively attack tumor cells.

Scientists can knock out genes in the T-cells that inhibit their cancer-fighting ability, creating stronger, more persistent immune cells (CAR T-cells).

L. Disease Modeling in Labs

CRISPR is transforming Disease Modeling in Labs. Researchers can easily create precise genetic mutations in cell lines or laboratory animals (like mice) to accurately mimic human diseases.

This allows for the rapid testing of new drugs and therapies in a genetically relevant system before human trials.

M. Diagnostic Tools (CRISPR-Dx)

New developments focus on Diagnostic Tools (CRISPR-Dx). Certain Cas enzymes (like Cas12 and Cas13) can be repurposed to quickly and accurately detect specific DNA or RNA sequences.

This technology is being adapted for rapid, low-cost detection of infectious diseases, including COVID-19, and cancer biomarkers.

N. In Vivo vs. Ex Vivo Delivery

Success depends on *In Vivo* vs. *Ex Vivo* Delivery methods. Ex vivo involves editing cells outside the body, which is safer but more complex.

In vivo delivery, where the CRISPR components are directly injected into the body (often via viral vectors), is necessary for treating organs that cannot be easily accessed, like the brain or liver.

4. Expanding CRISPR Beyond Medicine

The impact of CRISPR extends far beyond the human body, offering unparalleled opportunities to improve food security, enhance global ecosystems, and accelerate biological research across all domains.

CRISPR is quickly becoming a critical tool for agriculture and environmental science.

O. Engineering Crop Resilience

CRISPR allows for Engineering Crop Resilience to climate change and disease. Scientists can precisely modify genes to make crops like wheat and rice resistant to drought, specific pests, or herbicides.

This precision editing is far faster and more controlled than traditional breeding methods, dramatically shortening the time to market for improved strains.

P. Nutritional Enhancement

The technology is used for Nutritional Enhancement in food sources. Examples include increasing the nutritional value of vegetables or eliminating undesirable compounds like allergens in peanuts.

The ability to make precise modifications avoids the ethical and regulatory hurdles sometimes associated with adding foreign genes (transgenes).

Q. Gene Drive Technology

A controversial but powerful application is Gene Drive Technology. This method uses CRISPR to ensure a specific gene modification is inherited by virtually all offspring, accelerating the spread of the modification through a population.

Gene drives could be used to wipe out disease-carrying pests, such as mosquitoes that transmit malaria or Zika virus.

R. De-Extinction Possibilities

CRISPR opens the door to De-Extinction Possibilities. Scientists are exploring using the technology to insert genes from extinct species (like the woolly mammoth) into the genome of their living relatives (like the Asian elephant).

This complex process is fraught with ethical and ecological concerns regarding the reintroduction of extinct species into modern ecosystems.

5. Ethical and Safety Considerations

The immense power of CRISPR mandates a parallel focus on the ethical implications, particularly regarding unintended consequences, equity, and the concept of germline editing.

The responsibility of editing the human genome requires careful global governance and reflection.

S. Off-Target Effects

A primary technical concern is Off-Target Effects. Cas9 is highly specific, but it can occasionally cut DNA at sites that closely resemble the target sequence, leading to unintended mutations elsewhere in the genome.

Ongoing research focuses on engineering Cas variants and delivery methods to improve fidelity and minimize these unwanted cuts.

T. Germline Editing Debate

The most profound ethical issue is the Germline Editing Debate. This involves editing reproductive cells (sperm, eggs) or early embryos, ensuring the change is inherited by all future generations.

While it offers the possibility of eradicating inherited diseases forever, it raises concerns about safety, consent for future generations, and the potential for creating “designer babies.”

U. Equitable Access

There are major concerns regarding Equitable Access to these life-saving therapies. Given the high cost of developing and administering complex gene therapies, ensuring fair access across different socioeconomic groups and nations is critical.

The danger of exacerbating existing health inequalities is a persistent ethical challenge.

V. Regulatory Oversight

The technology requires robust and flexible Regulatory Oversight. Governments and international bodies must develop clear, adaptable guidelines that promote beneficial research while strictly controlling risky or irreversible applications, particularly germline editing.

Public trust in the technology relies heavily on transparent and responsible regulation.

6. Next-Generation CRISPR Tools

The initial Cas9 system is continuously being refined and expanded with new Cas variants and editing tools that offer even greater precision, versatility, and efficiency than the original molecular scissors.

The CRISPR toolbox is rapidly expanding, offering more control and less risk.

W. Base Editing

A major refinement is Base Editing. This technique modifies a single nucleotide (a base) without cutting the double helix, changing one letter (e.g., A to G) directly into another.

Base editing significantly reduces the risk of off-target cuts and the unpredictable errors associated with the NHEJ repair pathway.

X. Prime Editing

The latest innovation is Prime Editing. This system uses a reverse transcriptase enzyme coupled with a modified Cas9 to insert or delete sequences up to dozens of base pairs long, all without making a double-strand break.

Prime editing is considered the ultimate “search and replace” tool, offering unparalleled precision for correcting point mutations and small insertions.

Y. Cas12 and Cas13 Systems

Other enzymes, such as Cas12 and Cas13 Systems, are being utilized. Cas12 targets DNA with different PAM requirements, offering more target options, while Cas13 targets and cuts RNA instead of DNA.

RNA editing with Cas13 offers the advantage of temporary, reversible changes, making it ideal for therapeutic applications where permanent changes are not desired.

Z. Epigenetic Editing

Emerging tools allow for Epigenetic Editing. Instead of changing the DNA sequence itself, these tools modify chemical tags attached to the DNA (epigenetic marks) that control whether a gene is turned on or off.

This offers a way to control gene expression without causing irreversible changes to the genetic code.

Conclusion: Shaping the Future of Biology

CRISPR Technology has irrevocably altered the landscape of molecular biology, transitioning the field from cumbersome genetic manipulation to elegant and precise genome editing. The ingenious system, borrowed from bacterial immunity, relies on the customizable guide RNA to target DNA, and the Cas9 enzyme action to execute a clean, precise double-strand break.

This precision unlocks incredible potential for gene therapy for inherited disordersand significantly enhancing cancer immunotherapy. Despite the immense therapeutic promise, the ethical dilemma of germline editing debate and the necessity of equitable access require responsible global governance. Continuous innovation in base editing and prime editing is refining the technology, making it safer and more versatile for all applications.