Epigenetic Revolution: Environment Affects Your Genes

Introduction: Beyond the DNA Blueprint

For most of the 20th century, the foundational understanding of life was anchored in genetic determinism, the seemingly unshakable belief that an organism’s traits, health risks, and destiny were rigidly sealed within the fixed sequence of its DNA blueprint. The discovery of the double helix and the subsequent mapping of the human genome reinforced the idea that our biological story was entirely written by the four nucleotide “letters” (A, T, C, G) we inherited from our parents. However, the last few decades have unveiled a far more nuanced and dynamic reality, revealing a complex layer of cellular memory that operates above the genetic code—a phenomenon aptly named Epigenetics (from the Greek prefix epi- meaning “on top of” or “in addition to”). This revolutionary field demonstrates that while the DNA sequence itself remains constant, various environmental factors, lifestyle choices, and even social experiences possess the remarkable ability to modify how those genes are actually read and expressed.

Epigenetics essentially provides the operating instructions for the genome, determining which genes are actively turned “on” and which are “turned off” in different cells, at different times, and in response to external signals. These modifications are chemical tags and structural changes that attach to the DNA or the surrounding proteins, acting like dimmers and switches that control the volume of gene expression without ever altering the underlying genetic text. This profound mechanism explains why identical twins, who share $100\%$ of their DNA, can develop different diseases, and how a mother’s diet during pregnancy can influence her child’s health decades later. The recognition that the environment wields such immediate and persistent control over our genetic destiny has completely transformed our approaches to medicine, nutrition, psychology, and evolutionary biology.

This extensive guide will delve into the core mechanisms of the Epigenetic Revolution, meticulously explaining the main molecular tools—such as DNA Methylation and Histone Modification—that govern gene activity. We will explore the compelling evidence linking lifestyle factors, including diet and stress, to epigenetic changes, and detail how these changes are implicated in complex diseases like cancer and diabetes. Finally, we will examine the exciting therapeutic frontiers that aim to harness the flexibility of the epigenome to rewrite our biological future.

1. Defining the Epigenetic Landscape

The concept of epigenetics is centered on the biological mechanisms that control gene activity without necessitating a change in the underlying sequence of the DNA itself.

Epigenetics is the software that tells the genetic hardware when and how to run.

A. The Core Distinction

The primary point is The Core Distinction between genotype and phenotype. The genotype is the inherited, fixed DNA sequence, while the phenotype is the observable characteristic or trait.

Epigenetics influences the phenotype by regulating gene expression, acting as the bridge between the stable genotype and the flexible, environment-influenced trait.

B. Gene Expression Regulation

Epigenetic mechanisms control Gene Expression Regulation. Every cell in the body contains the same full genome, but skin cells look different from nerve cells because they express a different, highly specialized subset of those genes.

Epigenetic tags ensure that only the genes necessary for a specific cell type’s function are active.

C. Heritability of Epigenetic Marks

A critical aspect is the Heritability of Epigenetic Marks. Unlike transient signals, epigenetic changes can be stable and maintained through cell division (mitosis).

Crucially, some epigenetic marks can even be passed down from parent to offspring (transgenerational epigenetic inheritance), influencing the next generation’s health.

D. Plasticity and Reversibility

The epigenome is characterized by Plasticity and Reversibility. While the DNA sequence is permanent, epigenetic marks are dynamic and can be added, removed, or modified in response to new environmental cues.

This inherent flexibility makes the epigenome a prime target for therapeutic interventions designed to “undo” harmful modifications.

E. Developmental Timing

Epigenetic control is crucial for Developmental Timing. The cell uses specific epigenetic marks to ensure that different genes are activated or silenced at precise moments during embryonic development and maturation.

This tightly regulated process ensures that specialized organs and tissues form correctly at the right time.

2. The Molecular Tools of Epigenetic Control

Three main molecular mechanisms serve as the primary tools for the cell to mark the genome, acting as the chemical switches that silence or activate specific regions of the DNA.

These molecular mechanisms form the complex language of the epigenome.

F. DNA Methylation

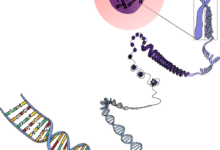

The most well-studied mechanism is DNA Methylation. This involves adding a small chemical group—a methyl group—to the cytosine bases (C) in DNA, usually at CpG sites (C followed by G).

Heavy methylation typically acts as a lock, physically blocking the transcriptional machinery from reading the underlying gene, effectively silencing it.

G. Histone Modification

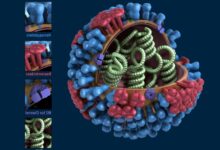

Another crucial process is Histone Modification. DNA is tightly wrapped around proteins called histones to form chromatin, the condensed structure within the nucleus.

Chemical tags (like acetyl, methyl, or phosphate groups) can be added to the histone tails, altering how tightly the DNA is packed.

H. Chromatin Remodeling

Changes to histone tags lead to Chromatin Remodeling. When histone tails are acetylated, for instance, the chromatin structure loosens, making the DNA more accessible for gene transcription (gene activation).

Conversely, deacetylation causes the chromatin to condense, making the gene inaccessible and turning it off.

I. Non-coding RNA (ncRNA)

The third major layer involves Non-coding RNA (ncRNA). These RNA molecules, such as microRNAs (miRNAs) or long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), do not code for proteins but regulate gene expression.

They can bind to messenger RNA (mRNA) to prevent protein production or interact with chromatin to directly promote or suppress transcription.

J. The Epigenetic Clock

These marks form the basis of The Epigenetic Clock. Scientists have identified specific methylation patterns that reliably track an individual’s biological age (the rate of cellular aging) better than their chronological age.

This clock is a powerful biomarker for predicting health span and disease risk.

K. Writers, Erasers, and Readers

The epigenetic system is managed by enzymes classified as Writers, Erasers, and Readers. Writers add the tags (e.g., methyltransferases), erasers remove them (e.g., demethylases), and readers interpret the tags to promote or suppress gene expression.

The balance and activity of these enzyme families are critical determinants of the cell’s gene expression profile.

3. Environmental and Lifestyle Influences

The power of the epigenome lies in its sensitivity to external factors, proving that our daily choices and immediate surroundings have a profound, long-lasting impact on our genes.

What you eat and how you live actively dictates your gene expression profile.

L. Diet and Nutrients

Diet and Nutrients are powerful epigenetic modulators. Certain components, particularly folate and vitamin B12, act as sources of methyl groups, directly influencing DNA methylation patterns.

For example, a mother’s diet rich in methyl donors can alter the gene expression profile of her developing fetus.

M. Stress and Early Life Trauma

Stress and Early Life Trauma cause rapid, profound epigenetic changes. Exposure to severe stress, especially during critical developmental periods, can alter the methylation patterns of genes involved in stress response, like the glucocorticoid receptor gene.

These changes can lead to lifelong alterations in anxiety levels and stress resilience.

N. Exercise and Metabolism

Exercise and Metabolism also induce significant epigenetic effects. Physical activity can rapidly alter the methylation status of genes in muscle tissue, optimizing muscle growth and metabolic efficiency.

This demonstrates a direct molecular link between lifestyle and cellular function.

O. Toxins and Chemical Exposure

Toxins and Chemical Exposure can wreak havoc on the epigenome. Exposure to heavy metals or endocrine-disrupting chemicals can interfere with the enzymes that regulate histone and DNA modifications.

These disruptions are linked to increased risks of cancer and developmental abnormalities.

P. Social Bonding and Nurturing

Studies on Social Bonding and Nurturing in animals show clear epigenetic effects. Pups raised by nurturing mothers exhibit different methylation patterns on stress-response genes compared to those raised by neglectful mothers.

This research highlights how behavior can be chemically encoded into the epigenome.

Q. Circadian Rhythm Disruption

Circadian Rhythm Disruption from shift work or poor sleep also impacts the epigenome. The genes that control our internal body clock are themselves regulated by epigenetic marks.

Disrupting these marks through chronic sleep deprivation can negatively affect metabolic function and increase disease vulnerability.

4. Epigenetics and Disease Mechanisms

The flexibility of the epigenome means that epigenetic errors are frequently implicated in the onset and progression of many complex, non-communicable diseases, offering new insights into pathology.

Epigenetic dysregulation is a common feature across many chronic illnesses.

R. Cancer Pathogenesis

Epigenetic errors are central to Cancer Pathogenesis. A common feature in many tumors is global hypomethylation(loss of methylation) combined with localized hypermethylation (excessive silencing) of tumor suppressor genes.

The loss of methylation promotes instability, while the silencing of protective genes allows unchecked cellular growth.

S. Neurodegenerative Disorders

Neurodegenerative Disorders like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s often involve epigenetic dysregulation. Changes in histone acetylation are linked to the mis-expression of genes crucial for memory and neuronal health.

Restoring the balance of histone modification may be a key therapeutic strategy for these debilitating conditions.

T. Metabolic Disease (Diabetes)

Epigenetic marks link environment to Metabolic Disease (Diabetes). Poor diet and sedentary lifestyles can lead to changes in the methylation of genes controlling insulin production and glucose metabolism.

These modifications may explain why obesity and Type 2 Diabetes often run in families even without corresponding sequence mutations.

U. Autoimmune Conditions

Autoimmune Conditions like Lupus and Rheumatoid Arthritis also have epigenetic components. Certain immune cell types in affected individuals show characteristic patterns of DNA hypomethylation on genes that regulate immune activity.

This aberrant expression contributes to the immune system mistakenly attacking the body’s own tissues.

V. Infectious Disease Response

Epigenetics plays a key role in Infectious Disease Response. Viral infections can hijack the host cell’s epigenetic machinery to silence immune-response genes and promote viral replication.

Understanding these viral strategies can lead to new antiviral therapies that target epigenetic processes.

5. Epigenetic Therapies and Future Horizons

The reversibility of epigenetic marks makes them highly attractive targets for new medical interventions, moving beyond merely treating symptoms to potentially correcting the underlying cause of disease.

The next generation of drugs will be designed to selectively modify the epigenome.

W. Epigenetic Drugs in Cancer

Epigenetic Drugs in Cancer are already in clinical use. Drugs known as DNA methyltransferase inhibitors (DNMTi) and histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) work to reverse the silencing of tumor suppressor genes.

By chemically reactivating these protective genes, the drugs help the cell regain control over proliferation.

X. Precision Nutrition

The field of Precision Nutrition is being guided by epigenetics. Future dietary advice will move beyond generalized recommendations to include personalized plans based on an individual’s unique epigenetic profile and how their genes respond to specific nutrients.

Understanding these epigenetic responses can optimize health and minimize disease risk for individuals.

Y. Epigenetic Reprogramming

A major research frontier is Epigenetic Reprogramming. This involves using specific factors to “reset” the epigenetic marks of adult cells back to an embryonic or pluripotent state.

This reprogramming is key to regenerative medicine and could one day be used to grow new, healthy tissues for transplantation.

Z. Environmental Intervention

Epigenetics validates the power of Environmental Intervention. Since adverse epigenetic changes can be induced by lifestyle, favorable changes (e.g., intensive exercise, stress reduction, improved diet) can reverse those marks.

This gives individuals greater control over their long-term health prospects than previously believed.

6. Challenges and Complexities

Despite its revolutionary potential, the study of the epigenome faces significant challenges related to the complexity of the marks and the ethical implications of manipulating the source code of life.

The full picture of the epigenome is far more complicated than simple on/off switches.

AA. Epigenetic Noise

A key hurdle is distinguishing meaningful signals from Epigenetic Noise. Epigenetic marks vary significantly between different cell types, tissues, and even individual cells, making it difficult to pinpoint which changes are causative of disease versus which are merely consequential.

Advanced single-cell analysis techniques are required to overcome this complexity.

BB. Off-Target Effects of Drugs

Drug development must carefully address Off-Target Effects of Drugs. Epigenetic drugs are rarely precise, often affecting the expression of thousands of genes rather than just the intended target.

Designing drugs that selectively target specific epigenetic enzymes in specific tissues remains a major pharmacological challenge.

CC. Transgenerational Ethical Issues

The potential for Transgenerational Ethical Issues is significant. If adverse epigenetic marks induced by maternal stress or poor paternal diet can be passed to grandchildren, it raises questions about accountability and intergenerational health equity.

This emphasizes the need for a holistic view of health that extends across generations.

DD. The Epigenome Browser

Future research relies heavily on The Epigenome Browser. Large-scale collaborative projects aim to map the location and status of all epigenetic marks across all major human cell types.

Creating this comprehensive reference map is essential for interpreting clinical data and identifying therapeutic targets.

EE. Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS)

The scale of research requires Epigenome-Wide Association Studies (EWAS). These large cohort studies correlate disease status with specific patterns of epigenetic modifications across the entire genome.

EWAS are crucial for establishing correlations and identifying potential epigenetic biomarkers for early disease detection.

Conclusion: The Dynamic Destiny

The Epigenetic Revolution has fundamentally reshaped biology, confirming that our biological destiny is not sealed by the DNA blueprint but is dynamically regulated by the environment. This flexible control is executed through key molecular mechanisms, primarily DNA methylation and histone modification, which act as the cell’s dimmers and switches to govern gene expression regulation.

Compelling evidence demonstrates that lifestyle factors, including diet and nutrients and stress and early life trauma, directly induce changes to these marks. Epigenetic errors are now recognized as critical drivers in diseases ranging from cancer pathogenesis to metabolic disease (diabetes). The inherent plasticity and reversibility of these marks offer unprecedented therapeutic opportunities, driving research toward epigenetic drugs in cancer and the promise of precision nutrition.